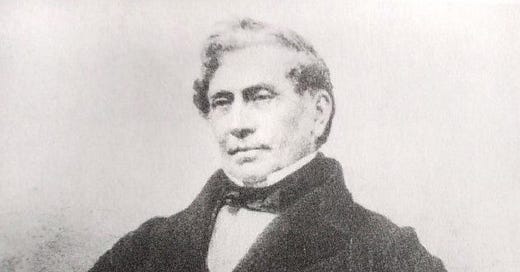

In an earlier newsletter, I recounted the story of Agnodice — the first female physician and midwife in ancient Athens who gained access to education and her own practice by dressing as a man. This weeks story is about Dr. James Barry (born Margaret Ann Bulkley) who dressed as a man in the 1800’s to obtain a medical degree from the University of Edinburgh Medical School.

Dr. Barry lived, practiced medicine, and died as a man. While there are speculations around his decision, his actions reflect someone who lived as male for the majority of his life and wished to be known as one after his death. So, in this story I will use male pronouns as well as the name Dr. James Barry.

Barry was born to a poor family in Cork, Ireland. His father ran a weighhouse at Merchant’s Quay until his dismissal from the position due to his anti-Catholic tendencies. He was later jailed for his debts. John Bulkley, Barry’s brother, was an apprentice to a lawyer in Dublin and married a woman of higher class in society after which he vanished, leaving Barry and his mother to fend for themselves.

Struggling to make ends meet, Mary Ann (Barry’s mother) reached out to her brother, James Barry, for help but he refused. However, upon his unexpected death from a respiratory disease, his estate was divided between Mary Ann and another brother. The profits from the sale of the estate were enough to secure Mary and Barry’s trip and lodgings in London.

In London, Mary planned for Barry, who was still living as a woman, to receive lessons from her brother’s friends in order to become a governess. While the initial plan was for this profession to be used as a source of income and a potential route to securing a husband for Barry, a plan quickly formed between him and his uncle’s friends (Daniel Reardon — the family solicitor, General Francisco de Miranda — whose son Barry tutored, and Dr Edward Fryer — Barry’s tutor). Having noticed Barry’s aptitude for learning, the three encouraged him to pursue a higher education in medicine — a task that was impossible for women at the time.

Following this plan, Barry and his mother cut all contacts with their old life (excluding the aforementioned friends), and traveled to Edinburgh. Barry began his studies at the University of Edinburgh Medical School as a literary and medical student. While he thrived during his years at medical school, his short stature and apparent lack of masculine features (including facial hair) led the university to believe he was a pre-pubescent boy not old enough to graduate. However, with the help of the eleventh Earl of Buchan (a friend of Dr. Edward Fryer), Barry was able to convince the medical board that there was no minimum age requirement for graduation. So in July of 1812, Barry received his MD.

Prior to his arrival in Edinburgh, Barry had reached an agreement with General Francisco de Miranda to join him in Venezuela and practice medicine there as a woman. However around the time of his graduation, General Miranda was betrayed and imprisoned until his death. As a result, Barry’s options were limited to returning to life as a woman, or continuing as a man in order to practice medicine. Whatever his motivation was, he chose the latter.

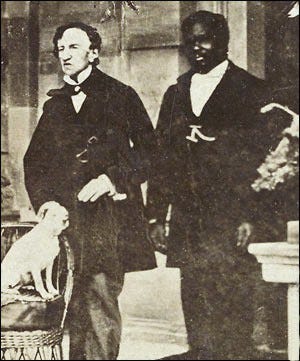

In 1813, Barry joined the British Army as a hospital assistant, was promoted to Assistant Surgeon of the Forces in 1815, and was sent to South Africa. There, Barry successfully treated the sick daughter of Lieutenant General Lord Charles Henry Somerset (the governor). Following the treatment, Barry became the governor’s personal physician and the two became close friends. In 1822, Somerset appointed Barry to be the Colonial Medical Inspector. This was quite the promotion given Barry’s low military rank, and rumors began to spread about his relationship with Somerset.

Unfazed by the rumors and excited about his new position, Barry quickly began implementing reforms including changing the sanitation process of the water systems, increasing the quality of care for the leper population, and requiring medical professionals to be licensed and certified. As is the case with all reform, Barry’s plans received a lot of pushback and as a result he made a lot of enemies. However, there was no question that he was a skilled doctor and surgeon. In 1826, Barry performed the first known successful C-section — a surgery that was, until then, solely used to deliver dead or live babies from dead mothers.

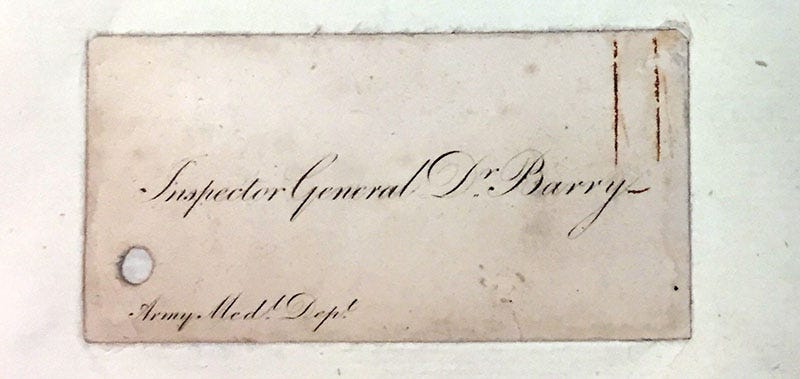

Following his success, Barry was promoted to Surgeon to the Forces and was often traveling to colonies such as Trinidad, Jamaica, and Malta to reform and manage disease outbreaks. After a visit to Corfu in 1851, he was promoted to Deputy Inspector-General of Hospitals — a position he kept until 1857 when he was posted to Canada and promoted again to Inspector General of Hospitals. Wherever he went, Barry advocated for better healthcare, housing, and treatment of under-represented groups and actively worked to improve the living condition of the people. In 1859, Barry was discharged after a long bout of bronchitis. He died from dysentery in 1865.

Barry’s wish was that his body not be examined and to be buried in the clothes he had died in. However, Sophia Bishop, a charwoman who had washed Barry’s body, visited the physician who had signed Barry’s death certificate (Staff Surgeon Major D. R. McKinnon) and claimed that his body was biologically female and had pregnancy stretch marks.

While her report was not authenticated by anyone, letters sent to Daniel Reardon connected James Barry to Margaret Ann Bulkley and to a third unnamed child, presented as Barry’s sister, but more likely Barry’s daughter as a result of sexual assault during his youth. Seeking a payout, Sophia attempted to blackmail Major McKinnon. When her attempt was unsuccessful, she sold the story — leading the British Army to seal all records of Dr. James Barry for the next 100 years.

There are a range of theories about Dr. Barry’s intentions behind living as a man, including that he was a hermaphrodite, that he was transgender, that he had followed a male lover to medical school, or that he wanted to be able to practice medicine making him the first woman to serve in the British military.

But we cannot, and should not, speculate about the private life of Dr. Barry. Had his wishes been respected and were it not for the greed of one, his gender would not have been a cause for conversation. Whatever the gender he identified with, we can agree with certainty that he was a skilled doctor and surgeon, and a passionate advocate for under-represented communities. He loved his work. He improved and saved the lives of many people. He was a humanitarian. That’s all we need to know.

I have no fun pun this week. Tell your friends to subscribe.